Diane Munday: I had an abortion when money made the difference between life and death

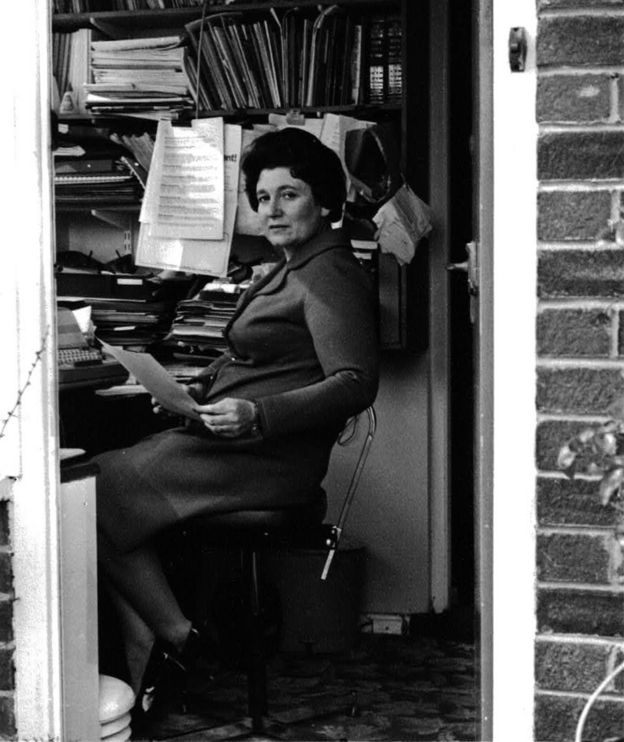

Diane Munday was the General Secretary of the Abortion Law Reform Association in the 1960s which helped make the 1967 Abortion Act possible. This piece was originally published by BBC News.

It wasn’t until I was about 21 years old that I first heard the word “abortion.”

In those days you had clothes made by a dressmaker and a local young married woman was making me a party dress; I went to her house for fittings. She had three young children and lived in a small post-war prefab house. I remember a very happy family. The father worked in a local factory and the children went to dancing lessons.

One day when I came home from work – I was a research assistant at Barts Hospital – my mother told me the dressmaker had died. I discovered she had had a backstreet abortion that went wrong. I hadn’t heard of this before – probably because the word was considered unmentionable. At that time a pregnant woman having an abortion and anyone who helped her could go to prison for it.

Then I discovered I was pregnant again – my fourth in three years – and something in me just said ‘I cannot, I will not have this child’

I was so shocked by this that I mentioned it to colleagues at lunch the next day. The doctors I worked with said it was a common experience and invited me to “stay behind on Friday evening and we’ll show you what the world is really like”.

I discovered then that all the London teaching hospitals set a few wards aside each Friday for women who were septic, bleeding or dying from having backstreet abortions. There would be a spate of cases on Friday because it was payday.

They were often performed by people with some nursing experience using hot solutions and knitting needles or coat hanger hooks. A big problem was their inability to diagnose the stage of pregnancy accurately and the more advanced a pregnancy the more dangerous what they did became.

Diane joined the Abortion Law Reform Society following the thalidomide scandal

I put the incident to the back of my mind and over the next few years got married and then had three children of my own (in less than four years – there was no “pill” back then). During my third pregnancy the doctor gave me a prescription for thalidomide because I had problems sleeping. I left it on the mantelpiece and did not take the drug.

The thalidomide scandal broke shortly afterwards and I got to thinking that if I had been carrying a deformed foetus I would have wanted the option of ending the pregnancy. So I joined the Abortion Law Reform Association (ALRA) but initially did no more than pay my membership fee. This organisation had been founded in the 1930s but it wasn’t really active as, post war, people preferred more polite social causes such as housing and education.

I became infamous – I was boycotted by the grocers in the village because they said my money was tainted

Then I discovered I was pregnant again – my fourth in four years – and something in me just said: “I cannot, I will not have this child.” My husband said he would much rather I continued the pregnancy but that it was my decision and he would support me whatever I decided.

After much asking around I found my way to Harley Street where there was a semi-legal procedure. The gynaecologist sent me to a friend who was a psychiatrist who said my mental health was so damaged by the pregnancy that my life was endangered. This was an accepted reason for an abortion because of a recent court case called the Bourne Case. It was only available to those who could afford to pay. I was quoted £150 – which was thousands in 1961 – but the doctor later halved it. He arranged for me to go to a private nursing home in north London

The procedure was done under general anaesthetic and I was in overnight. I found the nurses very unsympathetic – many of them disapproved because they were Roman Catholic. When I vomited due to the after effects of the anaesthetic, one nurse was extremely unpleasant.

Coming round from the anaesthetic, I remembered the young dressmaker who had died and realised how similar our situations were; we were both young women with three young children but where we differed was that , because I had a chequebook, I was alive and because she had no spare money she was dead. This seemed totally and unacceptably wrong. At that moment I vowed to myself that I would do everything I could to prevent women dying because they were poor.

So I went along to the next ALRA annual meeting, spoke to some people who had also joined because of the thalidomide scandal and within a year I was on the committee. That was when I started speaking out about abortion and that became my main role in the organisation.

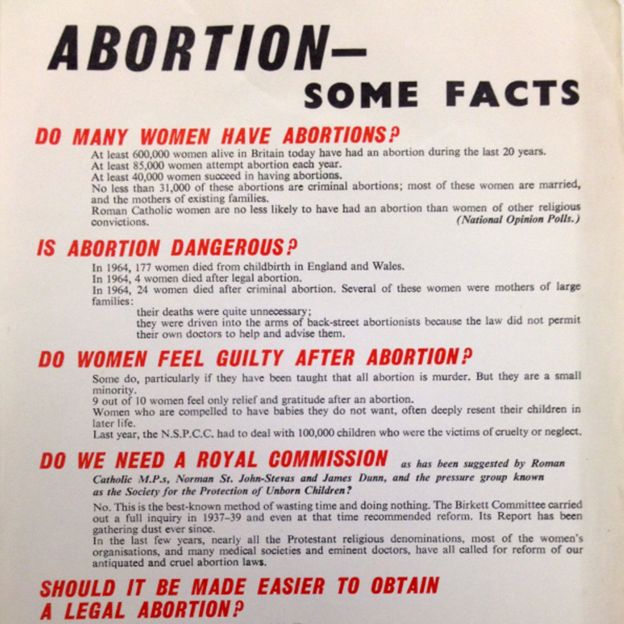

A poster from the 1960s printed by the Abortion Law Reform Association

I gave talks to groups and, from the start, decided to be open about it and say, “I have had an abortion.” I clearly remember an early Townswomen’s Guild meeting when, in the tea interval, members came up to me one after the other and said words to the effect of “You know dear, I had an abortion in the 30s. My husband was out of work and we couldn’t afford any more children.” From then on this was a common experience and I realised abortion was an unmentionable but routine part of women’s lives.

I became infamous. I was boycotted by the grocers in the village because they said my money was tainted – that I had been doing backstreet abortions on my kitchen table. My sons were affected by comments at school when I was on TV and I think my husband found it difficult.

But it needed to be done, the work was so important as women were desperate. They would try to self-induce by drinking gin, having scalding baths and moving heavy furniture around. Some travelled across the country and knocked on my front door as well as that of our secretary, Dilys Cossey, because her address was on the ALRA literature.

Despite being shunned by some in the village, women would come to me themselves or with their daughters when they were unmarried and pregnant. I’d drive them to a clinic and hold their hand while their daughter’s pregnancy was ended but next time I saw them they’d cross the road.

Later when ALRA needed money for its campaigning (it was run by unpaid volunteers) I approached the doctor who performed my own abortion to ask for a donation. It seemed to me that many doctors had benefited over the years and they could put some money back to help women who couldn’t afford fees. He agreed and also gave me names of other doctors who might contribute.

I asked him why he performed abortions and he told me that, when he was a young doctor, a patient said she would kill herself if she didn’t get an abortion. He told her the usual tale about loving the baby when it was born: that night she drowned herself and he felt that he had killed her.

Diane is concerned that there is still a taboo about admitting to having had an abortion

After much lobbying of MPs and a number of Bills in the Commons and the Lords the 1967 Abortion Act was passed. This was a great victory and a big step forward for women. But, for me, even then, it was not enough. I always believed that the only person qualified to make a decision about a pregnancy was the woman herself. We had had to make the concession that every abortion would be approved by two doctors. It was the price we paid for legalising any abortions at all. Nevertheless the beneficial effect was almost immediate with the numbers of women admitted to London hospitals for “septic miscarriages” dropping hugely within a year of the Act coming into effect.

But still there were battles to fight. Particularly in areas of the country where medical opposition to legal abortion had been most ferocious, surgeons said they wouldn’t perform abortions.

I helped set up the Birmingham (later British) Pregnancy Advisory Service to help women where NHS doctors refused to comply with the Act. Initially it opened as a counselling service in someone’s house. Women who could afford it were charged two shillings a visit and counselled and referred on to sympathetic doctors who would help them. This ensured that there was equitable treatment wherever somebody lived. Later, for 17 years, I worked for Bpas which had become a national organisation ensuring women were sympathetically and professionally treated wherever they lived and whatever the beliefs of local doctors.

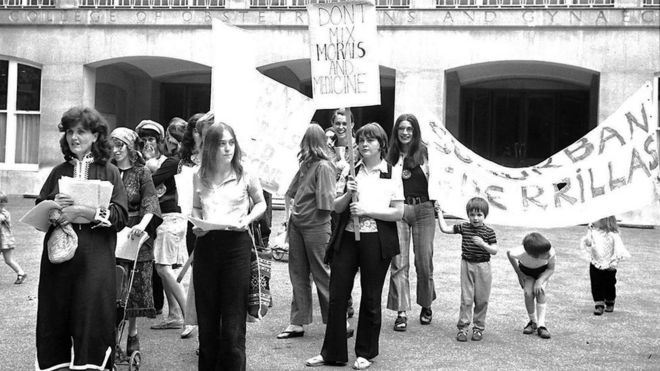

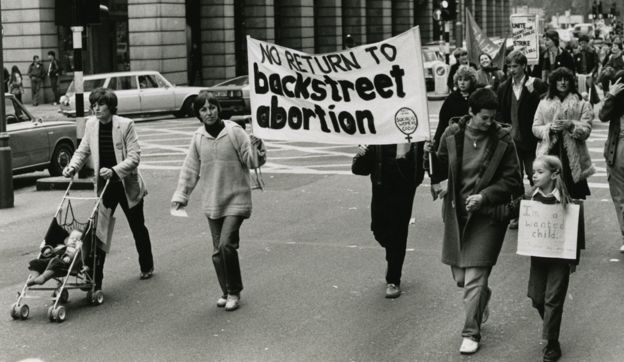

A London pro-choice rally in the 1970s

I’m proud of what I have done and of the benefits it has brought to so many women’s lives. However, my concern now is the future. There’s still a taboo around the subject making women reluctant to say: “I feel all right about having had an abortion.” Half a century after reform we live in a very different world. Women’s’ rights have moved on. Medical technology has moved on. But we still require two doctors to sanction the termination of a pregnancy that the pregnant women herself has decided on. It’s unbearable.

We were among the first in Europe to allow abortion and now are almost the last to have stringent laws controlling it. I would like to think that, before I die, the job I helped to start is finished by abortion being taken out of the criminal law and the decision as to whether or not a pregnancy is to be ended is firmly placed where it belongs – in the hands of the pregnant woman.

Diane Munday was interviewed by Claire Bates and Jane Garvey

Recent Comments